The Importance of the Revolutions of 1848 and the Paris Commune of 1871

Author: Jonathan Kočevar

Date: Monday, June 08, 2020

Russian Revolutionary Vladimir I. Lenin once said: “There are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen.” His quote perfectly encapsulates the setting in which Europe was situated before both the Revolutions of 1848 and the Paris Commune of 1871. Unregulated capitalism encroached on major cities, tight societal strains from the censorship of press to limited suffrage had been ingrained in society since the days of the Napoleonic Wars, and authoritarian regimes blanketed the map of Europe. Festering and breeding within the common populace in Europe was reform and revolution, and the revolutions of 1848 and the Paris Commune would radically change the social, political, and economic institutions entrenched in Europe since the early 19th century. The Revolutions of 1848 and the Paris Commune of 1871 have been immense to the development of economic and social revolutionary processes in the century following. This is seen through radical divide from the ruling governments of the time toward liberal and egalitarian philosophy, the political impact on living revolutionaries writings and ideological doctrine of the time, and the influence on future revolutions and struggles in the early 20th century.

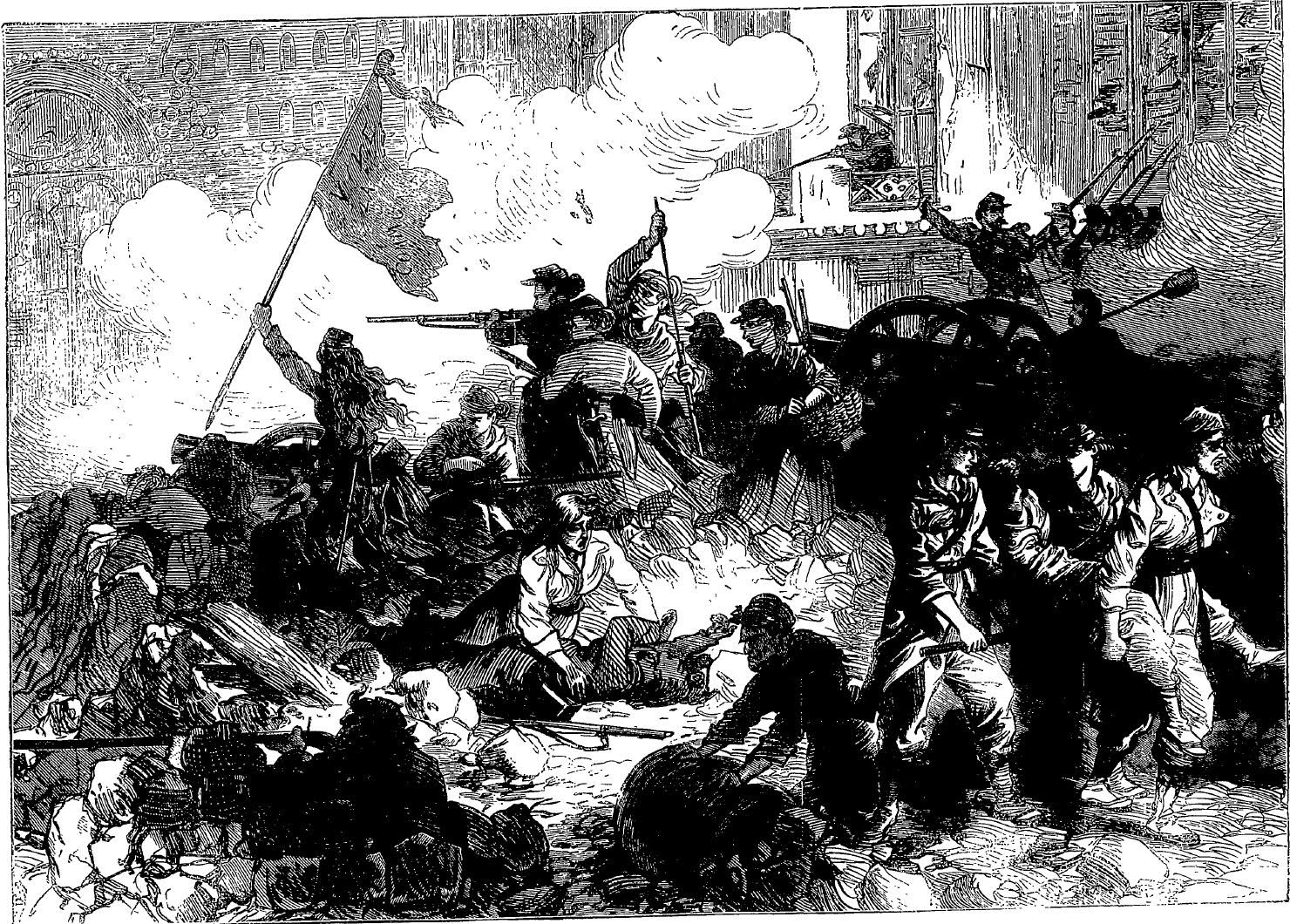

Firstly, the focus of social and governmental reform and distance from the past regimes can be seen in both 1848 and The Paris Commune. The divide from the social and political status quo of the time and the embracement of egalitarian ideals and democracy can also be seen in the Paris Commune. On March 26, 1871, The Commune, Splitting away from the French Republic, only a week old and without governance, had its first elections.1 Instead of beginning to build a formidable military and advance to the French provisional republic’s capital in Versailles, The Communards decided to focus on the interior. They held elections, passed laws, and sent delegations to other cities to join the Commune. Proudonists, a group of Proto-Socialists and Anarchists, took the center of the early Commune, passing bills to outlaw the death penalty, to institute the abolition of the military draft, and stalling the backwater of rent built up during the siege of Paris to all Parisians.2 The Communard Central Council ordered all workshops to be collectivized, seized and maintained by the workers and also initiated the reorganization to begin. The Council called for the workshops to be turned into worker cooperatives, democratically electing workers to become foremen and managers. The stride taken by the central council was applauded by many Parisian workers, one speaker saying “The day of justice approaches with giant strides… the workshops in which you are packed will belong to you; the tools that are put into your hands will be yours; the gain resulting from your efforts, from your troubles, and from the loss of your health will be shared among you. Proletarians, you will be reborn.”3 With both the status of the economy and the structure of the government and law changed in the Commune, the status of women was next. During the Commune, the lives of women were improved tenfold to before the insurrection. Elisabeth Dmitrieff, Communard and founder of the Union des Femmes, was quoted as saying that the women of the Commune could achieve “the creation of a new social order” based upon “equality, solidarity and of freedom.”4 Women pressured the central council for attention to be put towards their rights and for gender equality, many of which would be helping defend against the Versailles government on the barricades along with their male counterparts weeks later.5 During the last week of the Commune, named Bloody Week by the Communards and Parisians, hope of the new social order for women was on the edge of being crushed. A group of female Communards, mostly radical feminists called the Petroleuses took to the streets and began to burn many historic buildings that tied France back to the days of Bourbon rule. They had the objective of cutting ties to the oppressive structures that had held progressives back for the last century of French history, and spiting the Versailles government.6 It is coherent that both the revolutionaries of 1848 and the Communards enacted much social and political change around Europe.

Secondly, both revolutions would have an extreme impact on the ideologies and intellectual political radicals of the time, notably radical Socialist and Communist writers. Karl Marx, founder of communism and scientific socialism, was heavily influenced by his time both as a revolutionary during 1848, and as a witness to the 1871 Commune. In the aftermath of 1848 and the failed German Communist League and Belgian workers insurrection that Marx had supported fervently, Marx began to change his views and cement them in practical ideals learned during his work with the German Communist League. Marx saw from his time watching the revolutions of 1848 and believed that the only way to overthrow the capitalist threat was his idea of permanent revolution. In his book The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. Marx writes,

“As soon as one of the social strata above it gets into revolutionary ferment, the proletariat enters into an alliance with it and so shares all the defeats that the different parties suffer, one after another. But these subsequent blows become the weaker, the greater the surface of society over which they are distributed. The more important leaders of the proletariat in the Assembly and in the press successively fall victim to the courts, and ever more equivocal figures come to head it.“7

Marx believed that every time a revolution had begun, the working class and its representatives allied themselves with Liberal Democrats and the upper classes to overthrow the government, only to later take many of the blows in men and leadership and be betrayed by the upper class once a liberal democracy. Marx theorized this from his views of the February revolution of 1848 in France, which consolidated into a liberal democracy allowing Louis Napoleon III to take power, isolating many of the Socialist and Communist proletariat that helped to overthrow the July Monarchy. After the Bloody Week of 1871 in the Paris Commune, Marx and many other mainly Communist and radical Socialist writers began to change their views on state power and revolutionary doctrines. Marx specifically would assess some of his earlier Socialist and Communist works, most importantly the idea that “the working class cannot simply lay hold of the ready-made state machinery, and wield it for its own purposes.”8 Marx decided that for a revolution to succeed or strive, the workers must smash the state and replace it with their own rather than take the structure of the old state and fill it, directly modeled on the Commune. Russian anarchist Mikhail Bakunin, father of anarcho-collectivism and rival of Marx, saw the Commune as, “a bold, clearly formulated negation of the State.”9 Bakunin had reaffirmed his view of organization against the state, and tried to spark another commune uprising in Lyon in the same year. It is clear that both the revolutions of 1848 and the Paris Commune in 1871 were extremely impactful on the political philosophers of the time.

Finally, the influence that the revolution of 1848 and the Paris commune had on future revolutions of the late 19th and early 20th century was enormous. The Revolutions of 1848, while being mostly repressed in Central Europe, had major effects on the state of France and the United States. In France, 1848 ushered an end to the July monarchy, and instituted a short-lived Second Republic, which would later consolidate in Louis Napoleon the third’s Second French Empire. The second empire would help unify Italy through various wars in the 1850s, liberating the people of Lombardy and Tuscany, aiding Italian nationalists to complete the Risorgimento, or plan to consolidate Italy. The Second empire would also take many initiatives to redesign Paris, turning it from a medieval city into a modern city, moving the impoverished Parisians to the outer arrondissements, or districts of Paris. This in turn caused strife and allowed revolutionary doctrines to be spread easier around the working men, being one of the main factors for the rise of the Paris Commune of 1871. The Revolutions of 1848 would be the precursor to the United States own revolution, the Civil war. After 1848, many of the revolutionaries became disillusioned with Europe after their goals were suppressed, and fled to the United States, where they would go on to preach for the freedom of Slavs in Austria, serfs in Russia, and the slaves in America.10 The Paris Commune influenced many socailist and Communist uprisings and revolutionary fervor. The most important event that the commune had influenced was the Russian revolutions of 1905 and 1917. The Revolution of 1905, caused by the loss of the Russians in the Russo-Japanese war saw many aspects taken from the Commune, notably the Chita Workers Republic in Siberia. The Revolution of 1917 saw the overthrow of the Tsars in Russia and leader of the Bolsheviks, Vladimir Lenin took many inspirations from the Commune. In his speech Lessons of the Commune, Lenin says,

“The Commune was a superb example of the great proletarian movement of the nineteenth century … The sacrifices of the Commune, heavy as they were, are made up for by its significance for the general struggle of the proletariat: it stirred the Socialist movement throughout Europe, it demonstrated the strength of civil war, it dispelled patriotic illusions, and destroyed the naïve belief in any efforts of the bourgeoisie for common national aims. The Commune taught the European proletariat to pose concretely the tasks of the Socialist revolution.“11

Commune iconography and ideas were highly idealized during the revolution and in the years after, with French Communists delivering Commune banners to the Russians and the Russians renaming the dreadnought Sevastopol to Parizhskaya Kommuna, or Paris Commune.12 In the early years of the Soviet union, the revolutionaries would try to model the country off of the Commune, but ultimately fail during Stalin’s reign.13 It is evident that the ideas and representation of the revolutions of 1848 and the Commune were both heavily influential on later revolutionary and reformist events.

In conclusion, both the Revolutions of 1848 and the Paris Commune of 1871 were watershed moments for the social, economic, and political landscape of Europe. They would institute the divide from traditionalist governance towards democratic and egalitarian society, impact influential political ideologues and radical philosophers of the time, and would go on to determine and model later revolutionary struggles in the early 20th century.

Works Cited

Donny Gluckstein, The Paris Commune: a Revolution in Democracy (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2011). ↩︎

Gluckstein, The Paris Commune: a Revolution in Democracy ↩︎

John M. Merriman, Massacre: the Life and Death of the Paris Commune (New York, NY: Basic Books, 2014). ↩︎

John Milner, Art, War and Revolution in France, 1870-1871: Myth, Reportage and Reality (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000) ↩︎

Merriman, Massacre: the Life and Death of the Paris Commune, 80 ↩︎

Gay L. Gullickson, Unruly Women of Paris: Images of the Commune (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1996). ↩︎

Karl Marx and Saul K Padover, “I,” in The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (Moscow, Central Federal District: Progress Publishers, 1937), pp. 9-9. ↩︎

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, The Civil War in France (Mansfield Centre, CT: Martino Publishing, 2014). ↩︎

Michail Aleksandrovic Bakunin, The Paris Commune and the Idea of the State (S.l.: B. Books, 1987). ↩︎

Curti, Merle. “The Impact of the Revolutions of 1848 on American Thought.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 93, no. 3 (1949) ↩︎

Vladimir Ilʹich Lenin, in Lenin Collected Works, vol. 13 (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1965), pp. 475-478. ↩︎

Bergman, Jay. “The Paris Commune in Bolshevik Mythology.” The English Historical Review 129, no. 541 (2014): 1412-441. Accessed June 10, 2020 ↩︎

Paul Saba, “The Paris Commune: First Proletarian Dictatorship,” The Paris Commune, accessed June 10, 2020 ↩︎