Politics and Religion in Ancient Rome

Author: Jonathan Kočevar

Date: Sunday, April 03, 2022

Apollo, Jupiter, Mars, Juno. Infamous and well known gods of the even more infamous state of Rome, one of the largest geopolitical entities of its time. The religion and spiritual tales of Rome were a large inspiration and influence on the leaders and administrators of the state through its existence. Of the three periods of Roman political history, those being the Regal, Republican, and Imperial periods, religion and spiritual beliefs in Rome played a large part in the ever shifting nature of Roman politics and governance throughout its history.

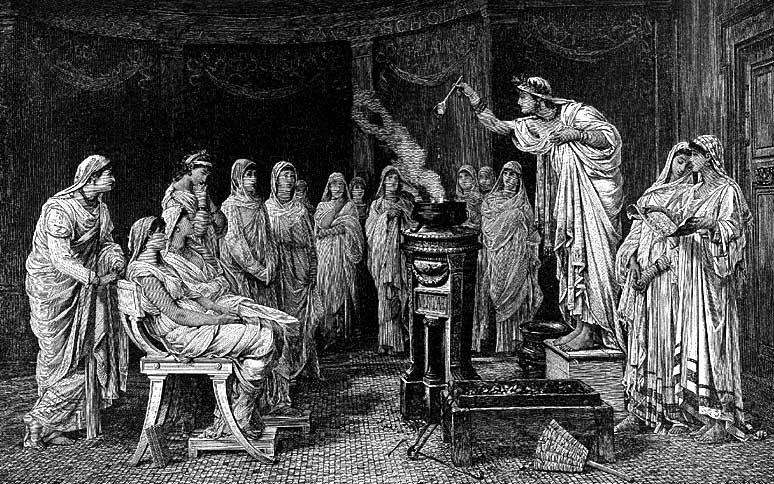

In the early years of the Roman state, the years of the reign of the mythical Romulus to Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, religion embeds itself as a deep part of Roman life and culture. While little records of the early kingdom’s history survive, oral lore and tradition documented by Roman and Greek historians such as Livy and Dionysius of Halicarnassus help to explain the importance of religion within the newly growing state. The introduction of many of the traditions of spirituality begin with its second King, Numa Pompilius. Departing from the founder and first King Romulus’s philosophies, Numa Popilius focused inward on Roman society and developing Roman religion. Numa began by redelegating many of the roles of the then unorganized religion of Rome, starting with appointing flamen, or priests, to the gods Jupiter, Mars, and Quirinus.1 In Livy’s great compilation of Roman history Ab urbe condita, he documents Numa Popilius’s creation of the priestesses of Vesta, also known as the Vestal Virgins, the infamous keepers of the sacred fire of Vesta and figureheads of the security of Rome.2 Numa Popilius is also known for the construction of the temple to the god Janus, which was used as a sign to the general public as an indicator of war within Rome, and with Numas reign “it was not seen open for a single day, but remained shut for the space of forty-three years together, so complete and universal was the cessation of war.”3 This shows a large sign of the early politics of Rome being deeply integrated with the presence of the gods and their will. Historian Plutarch writes of another office created by Numa, the Fetailes, which were a quasi-political priesthood, serving as diplomats calling on the gods’ approval when negotiations had gone hostile with surrounding tribes, even being the ones to produce the proclamations of war.4 With that, foreign relations of regal and early republican Rome would be under the hand of the Fetailes and the gods. It is clear that religion played a large part in early Roman kingship and political history, and was heavily intertwined with King Numa and his successors.

The emergence of new religious practices, especially from tribes and peoples conquered and politically subservient to Rome, started to blossom during the Republican Era. Greek gods such as Hera, Artemis, and Ares, were adapted by the Romans to the gods Juno, Diana, and Mars, the gods of state, hunt, and war respectively.5 The adaptation and expansion of worship of politically tied Greek gods to the early Roman republic coincides with the large conquests of early Rome, such as Magna Gracia, Macedonia, and Hispania. After the heavy political and military defeat at the battle of Cannae during the second Punic war, the Roman public saw itself not in favor with the gods. Upon the consulship of Gaius Claudius Nero and Marcus Livius in 207 BC, a series of religious appeasements were to be made, hoping to switch political favor of the gods back to the Romans.6 The sacrifice of 4 adult men to the gods was deemed as the solution by the pontiffs.7 With the favor of the gods, Roman political stability had been reestablished, and the following years after 207 BC would see Carthage pushed out of Italia and Hispania by the Romans until the end of the war in 201 BC.8 In the late republic, many notable families of Rome, such as the Antonius, Pompeia, and Julia traced their lineage back to certain gods as a political and prestigious tactic. For example, the son of Roman General Pompey the Great, Sextus Pompey, had “assumed a certain additional glory and pride by representing himself to be son of Neptune, since his father had once ruled the whole sea.”9 The notion of aligning oneself with the gods was a symbolic alignment of the family with the god’s powers and historic precedent for the family within the republic’s political apparatus.10

The Imperial Era of Roman history only continues the conjoining of state and politics with spirituality and religion. Many of the religious traditions started to become subservient, being either adapted or left behind to serve the Emperor’s political cause. Over the great transformative period that was Emperor Augustus’s reign, he looked to absorb sectors of the Roman religion into his rule. Directly after his settlement as Imperator, Augustus usurped the priestly title of Pontifex Maximus, a powerful Roman religious role and “decided to combine these two spheres symbolically by making part of his house on the Palatine Hill the official residence of the Pontifex Maximus.”11 This would make him a figurehead of political stability, as he had control over the election and appointing to the Vestal Virgins, who had since the origins of Rome been seen as icons of security and continuance of the Roman state.12 Beginning with Augustus and later strengthened by Emperors such as Diocletian, the formation of an Imperial cult, a mixing of the Emperors and the gods of Rome began.13 Much of the priests and Flamen from the Imperial Era, especially the Augustinian Era, were of aristocratic background, already serving in local imperial services and governmental positions. The political and religious structures merged through administration, as municipal nobles, doubling as flamen and priests, tended to both the imperial cult, and traditional Roman religious practices.

In conclusion, religion was a decisive factor when regarding the governance of man and politics during all eras of Rome’s history. Through analysis of the Regal, Republican, and Imperial Eras of Roman political history, it is evident that the religious sectors of Rome played a large part in both the guidance and structure of Rome politically.

Works Cited

Livy, Ab urbe condita 1.20.2 ↩︎

“In like manner he designated virgins for Vesta’s service —a priesthood, this, that derived from Alba and so was not unsuited to the founder’s stock. That they might be perpetual priestesses of the temple, he assigned them a stipend from the public treasury, and by the rule of virginity and other observances invested them with awe and sanctity."(Ibid. 1.20.3) ↩︎

Plut. Num. 20.4.2 ↩︎

“Roman Fetiales often went to those who were doing them a wrong and made personal appeals for fair treatment; but if the unfair treatment continued, they called the gods to witness, invoked many dreadful evils upon themselves and their country in case they resorted to hostilities unjustly, and so declared war upon them.”(Ibid. 12.4.1) ↩︎

John Scheid and Janet Lloyd, in An Introduction to Roman Religion (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2014), p. 179. ↩︎

(Livy, Ab urbe condita 27.37.1) ↩︎

“These prodigies were atoned for with full-grown victims, and a single day of prayer was observed by decree of the pontiffs. Then again the nine days of rites were repeated, because in the Armilustrium men saw a rain of stones.” (Ibid. 27.37.4) ↩︎

Adrian Goldsworthy, in The Fall of Carthage: The Punic Wars 265-146 BC (London: Phoenix, 2009), p. 245. ↩︎

L. de Blois and Peter Funke, in The Impact of Imperial Rome on Religions, Ritual, and Religious Life in the Roman Empire: Proceedings of the Fifth International Network, vol. 5 (Leiden: Brill, 2006), p. 24. ↩︎

Edwin White Webster, in Virtus and Libertas: The Ideals and Spirit of the Roman Senatorial Aristocracy from the Punic Wars through the Time of Augustus (Chicago, Ill, 1936), pp. 29-30. ↩︎

Werner Eck, in The Age of Augustus (Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Pub., 2007), pp. 74-75. ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎

L. de Blois and Peter Funke, in The Impact of Imperial Rome on Religions, Ritual, and Religious Life in the Roman Empire: Proceedings of the Fifth International Network, vol. 5 (Leiden: Brill, 2006), pp. 41-42. ↩︎